Panday explainer

The evidence suggesting that Johan Booysen was initially reluctant to pursue Thoshan Panday to protect Bheki Cele, a man who was instrumental in Booysen’s promotion, then opportunistically going after Panday to cast himself as a whistle blower being unfairly prosecuted, is as follows:

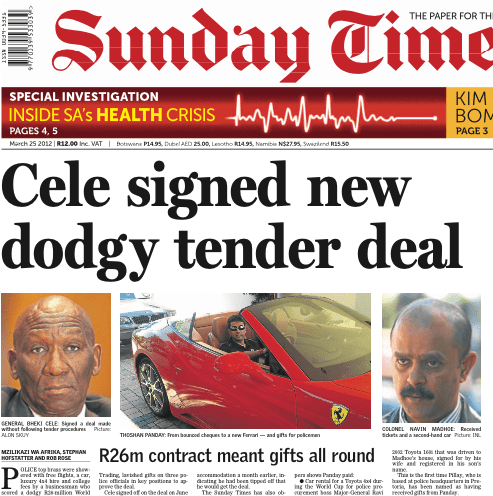

- Bheki Cele personally signed off on the clearly corrupt R60 million contract awarded to Thoshan Panday for 2010 World Cup police accommodation. Together with my colleagues at the Sunday Times, I wrote the first detailed exposé of the Panday corruption case a few months after we wrote our first Cato Manor story. This in itself renders absurd the argument sometimes made that we wrote the Cato Manor story to derail Johan Booysen’s investigation into Panday.

- Booysen issued an instruction that the main investigator in the Panday case, Colonel Vassan Soobramoney, should return the file to him just three days after the case was opened. Soobramoney was very unhappy with Booysen’s instruction, so he made a private copy of his files before handing them to Booysen, and reported Booysen’s interference to the chief of the Hawks, Anwa Dramat. Dramat instructed Soobramoney to continue the investigation. It was only when Soobramoney reported this to Booysen, that Booysen gave him his blessing to continue. Even then, Booysen did not return his files (see Soobramoney affidavit, 19 January 2012).

- By August 2010 Soobramoney had gathered enough evidence for Panday to be prosecuted. An inventory of the evidence listed 34 hardcover books, 44 lever-arch files, 293 folders with documents, 19 exhibit bags with loose documents, and 4 CDs of phone records. It was enough for 141 counts of fraud and corruption against Panday. All that remained was for a forensic auditor to draw up a report reconciling inflated payments made to Panday with gratuities paid to police procurement officials (see SAPS memo, 17 August 2010).

- Shortly after this, as the Zondo commission has heard, Soobramoney was removed from the scene through machinations by Richard Mdluli, the former head of crime intelligence. But far from taking any vigorous actions to expedite the case, Booysen seem to slow it down. He appointed a small local audit firm, which was fired a year later, after failing to deliver its report.

- In September 2011, a full year after Soobramoney had gathered enough evidence to proceed with prosecuting Panday, Booysen was approached by a shady police procurement official, Navin Madhoe, who was in cahoots with Panday. Madhoe tried to bribe and intimidate Booysen into derailing the Panday case. This was an ill-considered move. Now Madhoe and Panday had to be neutralised because they held evidence that could incriminate Booysen. By rejecting their bribe attempt and reporting it, Booysen was able to cast himself as a clean cop being targetted for blowing the whistle on corruption. This, in my opinion, was necessary for Booysen to save his own skin, even if it risked incriminating his alleged benefactor, Bheki Cele.

- Next Booysen appointed PwC to produce the forensic report. PwC spent another three years essentially duplicating Soobramoney’s work, and coming the same conclusions he’d reached in August 2010.

- In essence, Booysen’s actions point initially to a containment strategy to prevent the prosecution of Thoshan Panday because it would implicate his alleged benefactor Bheki Cele, then opportunistically reporting the Madhoe/Panday bribe attempt to cast himself as a whistle blower being unfairly prosecuted.